Nobody knows who introduced garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) from Europe to North America, but whoever it was must have brought it for its flavor. Anyone who has smelled the crushed plant will understand why.

Despite its appealing scent and flavor, garlic mustard is, with good reason, among one of the most reviled plants on the continent. An aggressive invasive, it outcompetes native plants, dominates habitats, and is devilishly hard to eradicate. Is it possible to eat our way out of this ecological nuisance?

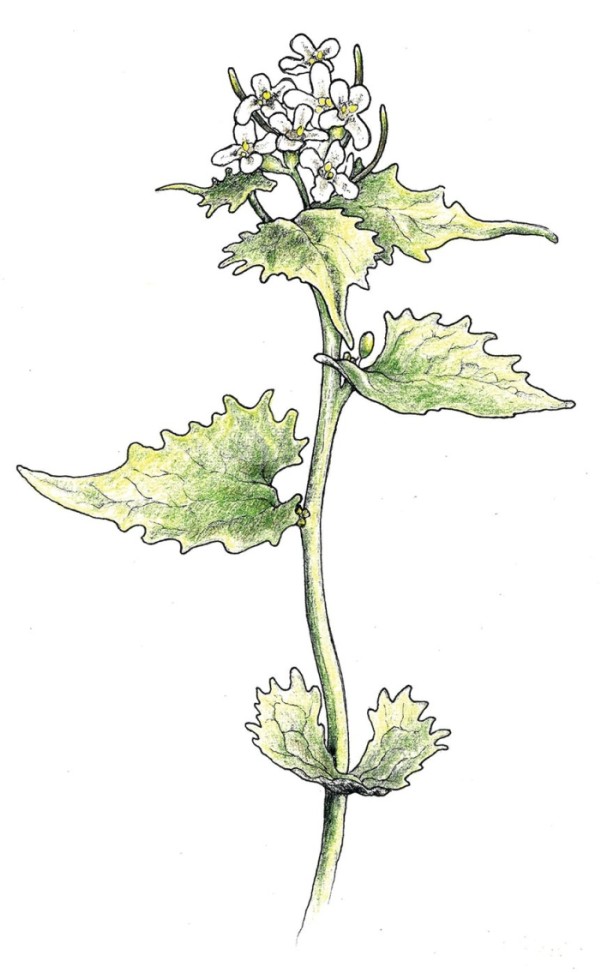

Finding garlic mustard is easy. It’s a common roadside weed. A biennial, garlic mustard grows as a rosette of long-stalked leaves in its first year, then sends up a straight, smooth, two- to three-foot stalk in its second. The stalk bears a cluster of small, white flowers. In common with the flowers of other plants in the mustard family, garlic mustard flowers have four petals and four sepals. These are arranged in an X.

The flowers, however, don’t bloom in the spring, considered by many to be the best time to harvest. So it is best to learn to identify the plant by leaves and stems alone. At first, this might seem challenging. The leaves are variable and can range from long-pointed to rounded. But other mustards tend to have narrower, more deeply lobed leaves. And none of them have garlic mustard’s unmistakable odor.

Over the years I’ve observed other foragers eat nearly every part of the garlic mustard plant: leaves, flowers, stems, and roots. They’ve claimed to enjoy them. Perhaps they have more robust palates than I. Personally, I find that most parts of garlic mustard are too bitter for my taste.

There is no shortage of advice about how to harvest garlic mustard leaves to minimize bitterness. Some say gather early. Others say gather in the shade. Some say gather only the second-year leaves. Others advise to avoid garlic mustard after it gets hot. I’ve not found any of these ideas to be helpful. Instead, I mostly avoid eating the leaves altogether, and just eat the stems. These I gather in mid-spring when the shoots are one-third to one-half of their total height. To test for tenderness, try breaking the stems and use only the ones that snap easily. Ones that don’t will be tough and stringy.

I keep the strong flavor of garlic mustard in mind as I prepare it. It is almost always better cooked, although a raw sprig goes a long way in a sandwich. The cooked and chopped shoots make a spicy addition to salads. They’re especially nice in creamy soups where their potency is offset by the fats in the cream.

Often when people new to foraging hear that a plant is edible, they imagine making it as a dish on its own or as the major ingredient in a salad. I have never really enjoyed garlic mustard as an asparagus-like side dish. Horseradish offers an instructive analogy here. I love horseradish, but I don’t eat it by the spoonful. I serve it on sausages or sandwiches. Garlic mustard is a great food to have in your foraging repertoire, but it works best as a condiment, not a vegetable.

Given the small quantities that I use, I am under no illusions that my foraging will help to control this pernicious invasive. Instead, I focus on weeding what I can, at sites where I want more native plants to flourish. I pull many times more plants than I use. Maybe someday garlic mustard will be controlled well enough that I won’t have to weed. Until then, a bagful of stems, chopped, fried, and added to a pasta sauce, is a tasty return for an ecological good deed.