For the past two years, from late fall to early spring, a livestream on the Finch Research Network’s (FiRN) YouTube page transported viewers to a snow-dusted yard in northern Maine. Through the lens of the FiRN camera, people could watch pine siskins, boreal chickadees, redpolls, and other winter avians as they perched at birdfeeders or rummaged for seeds on the ground. Viewers greeted each other in the chatroom and virtually gasped when the occasional owl swooped in for a chance at breakfast.

But no visitor prompted as much joy among viewers as the evening grosbeak (Coccothraustes vespertinus). Flocks of up to 20 birds huddled together on the platform feeders, the collective sound of their thick bills mincing seed hulls resembling the patter of graupel on pavement. Their striking yellow, black, and white plumage popped against the drab background of a New England winter landscape.

For many birders, the livestream (which FiRN plans to re-launch soon, in a new location) offered their best opportunity to watch these charismatic finches in real time. Evening grosbeaks have the unhappy distinction of being the fastest-declining landbird (bird that lives mostly over land) in the continental United States and Canada. Once common in winter across the northern tier and mountain ranges of the United States, the species’ population has plummeted. A 2008 study by the avian conservation group Partners in Flight indicated that evening grosbeaks no longer appeared at half of their historical sites and that flock sizes had shrunk by more than a quarter. Field reports also suggested a range contraction, with a significant drop in sightings of the species in the southern United States.

This decline has both puzzled and dismayed conservationists, who are hustling to understand the evening grosbeak’s full life cycle. Much is still unknown about the species’ behavior in its breeding habitat in old- and second-growth boreal forests, complicating efforts to promote recovery.

A Brief Evening Grosbeak History

The evening grosbeak is a comparatively recent arrival to the Northeast. Its core historical range stretched from the Pacific Northwest to western Canada. However, beginning in the late 1800s, the species began spreading east, and in some years, irrupting (moving south out of its typical winter range) down the eastern seaboard. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology attributes the grosbeak’s eastward tack to an expanded food supply provided in part by the widespread planting of boxelders, which hold their seeds all winter. By the 1920s, evening grosbeaks were common winter visitors to New England.

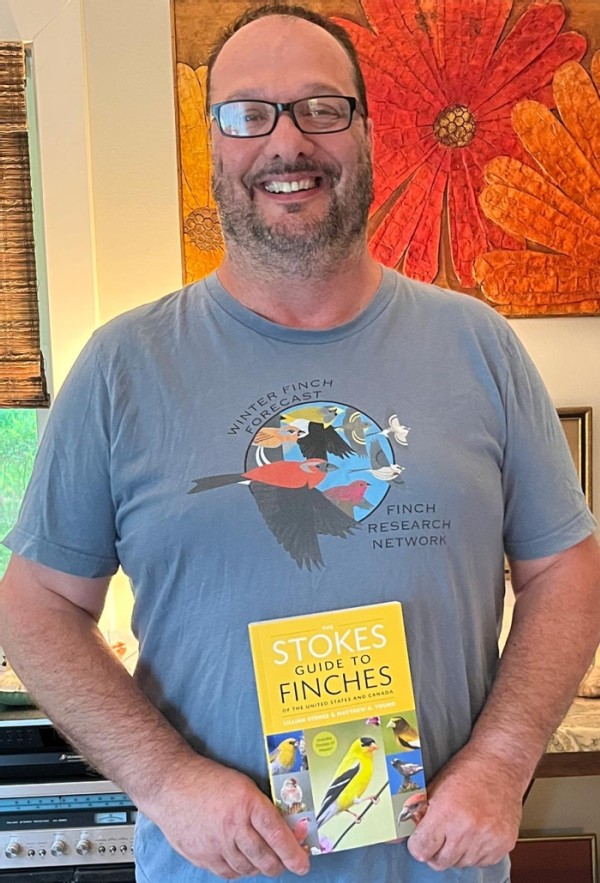

The eastern population crested in the later decades of the twentieth century. “In the East, from about 1965 to the mid-’90s, there were unbelievable numbers of them every winter, stretching all the way down to the Carolinas and sometimes farther south,” said Matt Young, the founder and president of FiRN. Young, who claims a “lifelong passion for finches” and recently published The Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada with Lillian Stokes, remembers when masses of evening grosbeaks flooded into the lower 48 states nearly every winter.

But declines across the bird’s range presaged trouble in the eastern population. Beginning in 1995, winter numbers in the eastern United States crashed. “The irruptions became barely noticeable. We got to a point where we were seeing almost no pulses,” Young said. This scarcity became the norm during the next two decades. It was clear that the irruptions were shrinking, but researchers did not have sufficient data from the bird’s remote breeding grounds farther north to say with certainty that the eastern population as a whole was ailing.

A groundbreaking report quantified the grosbeak’s range-wide woes. In September 2019, a team of Canadian and U.S. researchers, led by conservation scientist Kenneth Rosenberg from Cornell University, published an article in the journal Science that provided persuasive evidence that North America had lost nearly 3 billion birds since 1970. The scale of the losses varied across avian families, but the evening grosbeak’s freefall stood out. According to the researchers, the species suffered a 92 percent population reduction between 1970 and 2016, a period of a little less than 50 years.

The Science article set off a flurry of projects and calls to action to save North America’s birds. Among them was FiRN, which Young founded in 2020. Despite the evening grosbeak’s relatively recent shift into the East, the severity of its decline made it a natural focus for the new group. Additionally, the grosbeak shares its irruptive behavior and boreal breeding range with many of the other finch species within FiRN’s ambit, meaning that conservationists could use a better understanding of the grosbeak’s decline to help conserve other imperiled eastern birds.

But before FiRN could design a conservation strategy for evening grosbeaks, the group had to answer basic questions about their life cycle. And gathering data on the species is no small task. Irruptions are not in and of themselves clear evidence of a population increase or decline; they are influenced by multiple factors, including the availability of winter food in northern habitats. The birds’ movements and breeding densities change from year to year in different parts of their range, complicating efforts to monitor population sizes. And evening grosbeaks’ remote nesting locales deep in the boreal forest also present challenges for researchers.

Fortunately for Young and his colleagues at FiRN, others were already at work on a critical piece of the puzzle.

Gathering Data

David Yeany’s obsession with evening grosbeaks began in his childhood backyard. In 2007, while on a winter break from his graduate studies in ecology, he visited his parents at the family home just outside Allegheny National Forest in northwestern Pennsylvania. One day, he heard an evening grosbeak flight call. “I had never registered that species there,” said Yeany. With help from his father, he built a platform feeder, an attractive design for finches. By 9 o’clock the following morning, there were nine evening grosbeaks at the feeder, chomping on seeds. Nearly two decades later, the Yeany family’s backyard still hosts evening grosbeaks each year.

The species had not been a focus of Yeany’s ecology graduate studies before that winter. But thereafter, he was hooked. In 2016, as an avian ecologist in the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program at the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, he and a colleague began banding evening grosbeaks at sites in the national forest. The banding work, unprecedented for the species, was part of a small-budget pilot project to use nanotags to track the full annual range of evening grosbeak movements, including time spent in winter locations and the species’ presence in breeding habitat in boreal forests.

The project began as a scrappy affair. “We cobbled [it] together. We didn’t have dedicated funding,” Yeany said. Soon after Young launched FiRN in 2020, Yeany contacted him to share information about the banding effort in Pennsylvania, and the two began collaborating.

Despite these shoestring beginnings, the partnership was fortuitously timed to benefit from national attention and research funding focused on evening grosbeaks. In the fall of 2021, conservationists from across North America formed the Road to Recovery (R2R) program in response to the 2019 Science report. R2R selected the evening grosbeak for one of four pilot programs focused on “tipping point” species whose rapid declines were poorly understood.

R2R planners invited Yeany and Young to co-lead the pilot program. “It felt like a happy accident,” Yeany said. “I started by building this feeder in my dad’s backyard. Now, all of a sudden, we’re working on a continental project.”

Their mandate from R2R was to identify the principal factors behind the evening grosbeak’s losses in order to develop a strategy for the species’ recovery. “The hope is that we can come up with specific things we can do to stop the decline,” Yeany said.

Yeany and Young started by identifying five research priority areas: migratory connectivity and population dynamics, direct mortality (especially from window and vehicle collisions, cats, and disease), diet, habitat, and climate change. They established working groups for each of these elements and invited other conservationists, researchers, and avian ecologists to join the groups based on their respective specialties.

In a nod to his original banding project, Yeany co-leads the migratory connectivity and population dynamics working group. Funding from R2R allowed him to invest in new satellite transmitters, which provide more detailed data on the landscape movements of outfitted birds.

“By tracking individuals, we can see the paths that subpopulations are taking. Are they following certain land features? What habitats are they frequenting? We’re linking populations across their life cycle, from wintering to breeding,” Yeany said. “Once we ascertain how strong that linkage is, we’ll hopefully understand better how different threat factors influence the species.”

Identifying Threats

The list of potential “threat factors” is long. A key objective of Young and Yeany’s project is to identify which, if any, of these perils bear outsized responsibility for the evening grosbeak’s decline – and to predict how the risk landscape might change in the future.

One of the known factors affecting evening grosbeak numbers is a small – and in forestry circles, notorious – caterpillar: the spruce budworm. “We know budworm is a player, and that some of the declines were tied to the budworm’s management,” Young noted.

Budworm populations experience boom-and-bust periods, with major outbreaks occurring every 30 or 40 years. In high population years, the caterpillars offer a feast for evening grosbeaks and other boreal birds and may contribute to higher reproductive success rates.

A question that merits further study is whether efforts to suppress budworm populations are impacting the birds. In Canada and northern border states, governments and private timberland owners routinely spray budworm “hotspots” with pesticides and biological agents to protect fir and spruce timber stands. These treatments may negatively affect evening grosbeaks by reducing the abundance of budworms and other insect prey. Some sprays may also directly harm the birds’ health.

Another realm under investigation is direct mortality. For example, data from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) and the Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) have indicated that, based on the retrieval of dead banded birds, evening grosbeaks suffer from a “high” frequency of vehicular and window collisions. “They flock at feeders, so they’re often close to homes, which are the number one cause of window mortalities,” Yeany said. Their presence near homes also makes them vulnerable to cat predation, while the birds’ flocking behavior renders them vulnerable to avian diseases such as avian flu and West Nile virus.

There is also the impact of climate change.

“Climate change is really the elephant in the room,” said Young. “It’s hard to predict the effects, but the theory is that as the climate warms, these birds will recede farther and farther north.” Rising temperatures stress the boreal forests that grosbeaks prefer, and scientists project both balsam fir and spruce will shift north as global temperatures increase, potentially taking evening grosbeaks and some other boreal birds with them.

As New England winters continue to warm and more precipitation falls as rain rather than snow, Young’s concern is that the evening grosbeak, like other cold-adapted birds, will be especially vulnerable to stochastic events. For example, an increase in rainstorms in the winter months “can lead to isolated mortality events,” said Young. “It’s a lot harder for cold-adapted species to thermo-regulate in rain and ice in wintertime.” For a declining species such the evening grosbeak, a few untimely weather events can have major population impacts.

The science on exactly how – and on what timescale – climate change will affect evening grosbeaks is far from clear. “Some models say there could be a short-term gain or improvement in eastern numbers for a short period of time that precede declines farther down the road,” said Young. But research summarized in the December 2023 issue of Birding Magazine suggests that rapidly shifting weather patterns are already leading to reductions in irruptive species’ numbers.

Signs of Hope

The news isn’t all bad. After years of dismal sighting tallies in the Northeast, the winter of 2020–2021 offered a glimmer of hope.

“That was the biggest year since the decline started in the ’90s. Florida recorded its first grosbeak sighting since the early ’80s,” Young said. In winters since, observed numbers of birds have risen from the historic lows notched in the ’90s and 2000s. Young attributes the increase at least partially to ongoing spruce budworm outbreaks in Canada’s Quebec and Ontario provinces.

Although he’s pleased with this positive trend, Young cautioned that sightings remain low compared to what came before. “The numbers aren’t back to where they were in their heyday by any measure,” he said. “I haven’t seen anything remotely close to that.” He also noted that, based on tracking data accumulated by the R2R project, the species is faring poorly in some areas, even as it is increasing in others. “There are clusters of declines and increases across their range,” he said. For example, evening grosbeak populations in southern Quebec and the Gaspé Peninsula appear to be growing, while populations south of that appear to be in decline.

Still, Young is cautiously hopeful. “The numbers aren’t as high as 30 or 40 years ago, but they’re higher than 10 or 15 years ago,” he said. Many observers noted evening grosbeaks in breeding habitat in northern Maine this past summer, suggesting that 2024 may prove to be another comparatively good year.

As Young and Yeany wait to aggregate numbers from this winter, they remain focused on continuing to build out the R2R project. They hope to expand tracking work – so far limited to subpopulations in the Northeast and Midwest – to the Rockies and the Pacific Northwest.

When asked what kind of future they see for the evening grosbeaks of the Northeast, both Young and Yeany responded by offering their own questions. “Will parts of southern New York or northern Pennsylvania ever get back to that point where the species is around every winter?” asked Young. “We’re too early on at this point. I don’t know yet what the other side of this project looks like.”

“Will continuing spruce budworm outbreaks keep sending grosbeaks into the Northeast for decades to come? Or will changing weather patterns wash them out?” Yeany wondered. “It’s such a complex species that I hope in the next decade we’ll have a much better understanding of what’s going on and the direction of the trends.”

Although saving the evening grosbeak from extinction is the R2R subproject’s guiding purpose, Young emphasized that mobilizing conservationists and the general public to pay more attention to the birds is an important byproduct of the effort – and integral to its success. “We’re raising awareness so that people care. Part of the project is about bringing together as many stakeholders as possible,” he said. “That’s going to make the difference.”

Discussion *