Following the journey that forest products take to - and through - ND Paper's mill in Rumford, Maine.

I’ve always been fascinated by pulp and paper mills. There is something mysterious and imposing about them, with their tall, belching stacks, hissing steam vents, and the odors of the pulping process mixed with fragrant piles of wood, wood chips, and bark. Growing up near Berlin, New Hampshire, these were everyday sights and smells. I can remember how exciting it was to travel through town and see the trucks on their way to the wood yard, and it was common to be stopped for crossing trains as they headed into and out of the mill yard with supplies and materials. I used to try to count the number of train cars, and it was especially thrilling if the engineer leaned out the window and waved as he passed. My grandmother would sometimes drive my brother and me to the edge of the wood yard so that we could watch the trucks being unloaded and the bulldozers pushing up the chip pile.

But despite growing up in a mill town, living within a couple hours of several others, and having worked in the woods business for 20 years, I had never been inside one of these mills. What goes on behind the security gates, chain link fences, and windowless walls?

I had a chance to find out when I was invited by ND Paper’s U.S. Fiber Supply Director, Dave Harvey, to tag along with the Wadsworth Woodlands forestry team on a supplier tour of the company’s mill in Rumford, Maine. When I drove into the parking lot on a cloudy morning in early June, I found the place pulsing with energy and activity as the day shift arrived – those who worked in the yard, alongside well-dressed office employees and a maintenance crew that was beginning operations. The air was filled with the sound of engine brakes and downshifting as a steady stream of chip trucks drove onto the scales and tipped up nearly vertically to unload. A bulldozer was noisily clacking along high on the chip pile, while a train slowly moved across the yard with its horn blaring.

I met up with the tour group, and after introductions, our tour guides, pulpwood buyers Steve Pinkham and Fred Hellenberg, gave a brief background of the mill and their careers. Pinkham began working at the Rumford mill in 1990, when it was owned by Boise Cascade Company; he’d previously been employed at the James River mill in Old Town. When Pinkham arrived in Rumford, the facility employed 1,650. There are now only 650, and he explained that most of the downsizing is attributable to increased automation. In 2018, after a series of acquisitions and mergers, the Rumford mill was bought by ND Paper LLC, a subsidiary of Nine Dragons Paper Holdings Limited. The Chinese company currently operates 66 paper machines worldwide and owns additional US mills in Old Town, Maine; Biron, Wisconsin; and Fairmont, West Virginia.

Pinkham explained that the Rumford facility has 85 megawatts of steam generation capacity and generates much of the electrical load for the mill. Fuel for the fluidized bed boiler includes bark- and wood-processing residuals, biomass chips, chipped railroad ties (165,000 per year), rubber tire chips (equivalent to more than 10 million passenger car tires per year), sludge collected from the effluent streams, and coal. The cogeneration stack, built in 1989, includes an electrostatic precipitator that uses an electric charge to attract impurities to collection plates, which are then disposed of or recycled. On our visit, we couldn’t see anything coming out of the stack even though the boiler was running.

After introductions, our first stop was the wood yard. Many mills buy pulpwood in various lengths and debark and chip the wood onsite. The Rumford mill did that in the past, but currently it instead operates three satellite chipping plants in Shelburne, New Hampshire, and West Paris and Farmington, Maine. The mill also buys deliveries of clean sawmill chips from independent suppliers. The dumpers are open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and trucks are generally in and out in less than 20 minutes. The Rumford mill consumes roughly 1.7 million green tons of wood chips annually, approximately 40 percent softwood and 60 percent hardwood. Bark is also delivered from the chip plants and other sources to be used as boiler fuel. Softwood chips, hardwood chips, and bark are kept in three separate piles. ND Paper also buys more than 100,000 tons of aspen logs annually, which are processed directly across the road from the wood yard. The majority of the aspen comes from forests just north and east of the facility, but some comes from as far as 240 miles away.

The next step for the chips is pulping, a process that reduces wood to cellulose fibers by chemically dissolving the lignin. It is a complex process involving chemistry, large amounts of energy, and lots of water – millions of gallons per day. Because of that extensive water usage, the Rumford facility recycles water at its own treatment plant.

The kraft pulp making process used in Rumford and most modern pulp mills was invented in 1879. In highly simplified terms, the wood chips are cooked in a solution of sodium hydroxide and sodium sulfide – called white liquor – in pressurized containers called digesters. The Rumford Mill has a 90-foot tall continuous digester, which constantly has wood going into the top and pulp coming out the bottom. It takes two and a half hours for wood going in the top to come out as pulp. According to ND Paper’s internal communications contractor, Linda Pepin, the Rumford mill also has ten digesters that “process approximately ten truckloads of chips apiece each day. The digesters, standing three stories tall, are housed under one roof and it takes just under two hours to cook each batch of chips.”

After cooking, the pulp is washed, creating a byproduct called black liquor. ND Paper uses a closed-loop liquor cycle, in which the black liquor is burned in a recovery boiler. The organics are burned off, but the chemicals, after recharging, are reused. This continuous process, which allows mills to recycle almost all their pulping chemicals, was invented in the 1930s and was a major breakthrough in pulp-making. The pulp, at this point, is 96 percent water so that it can be pumped to other areas of the mill. It is brown, so it must undergo a bleaching process if it is to be made into white paper.

ND Paper Rumford also uses a mechanical pulping process in which aspen is ground to produce groundwood pulp. This process physically tears the cellulose fibers from one another. Each type of paper made at the mill has a recipe with different proportions of softwood, hardwood, and aspen. The ground wood pulp is used to give paper opacity so that print on one side is not visible on the other. It also helps create a smooth, flat printing surface. Mills not using a groundwood process will use other fillers like clay, titanium dioxide, or calcium carbonate for the same purpose. When we entered the computerized control room of the groundwood mill, the operators were getting ready to start back up after a short shutdown. They received their instructions from the supervisor, put on rubber boots and gloves, and began opening a series of valves before heading to their stations. Four-foot bolts of debarked aspen had been delivered by dump truck from the processing facility across the road and were waiting in a storage pond. The pieces were floated along a water-filled trough from which the workers, using picaroons, fed the bolts individually into hoppers leading to the grinders. After leaving the grinders, the pulp was screened before storage and mixing.

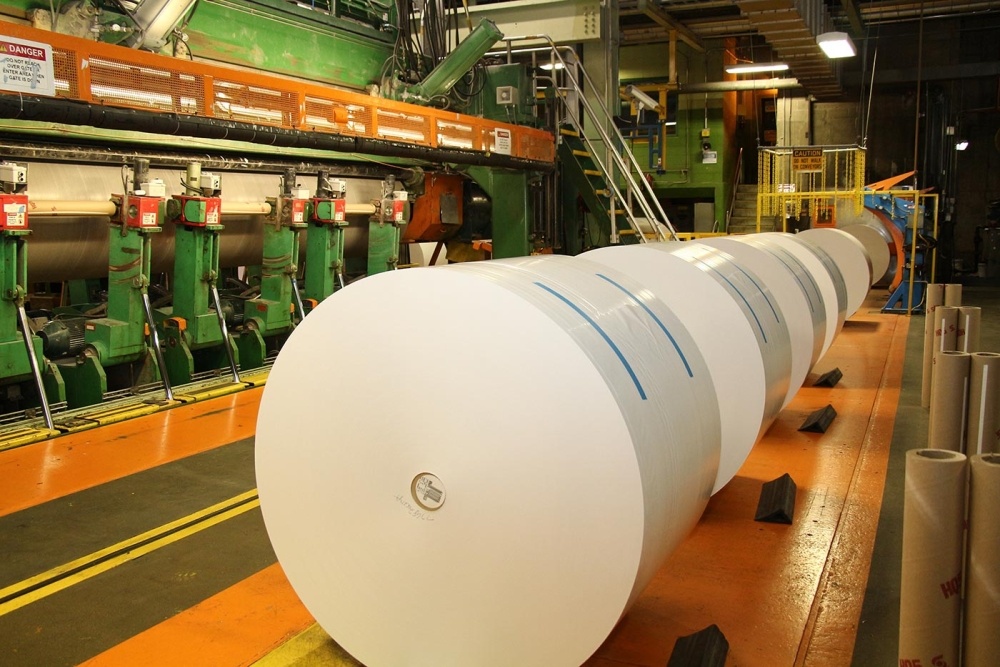

Commercial paper machines are massive and require very large, very long buildings to house them. Rumford has three such machines, which produce a total of 1,575 tons of paper per day. To simplify another complex process: paper-making begins with the liquefied pulp at what is called the “wet end” in the head box. The pulp is pumped onto a moving, woven mesh belt, where the fibers are aligned to create a paper web. The slurry then moves to a felt belt and a press section where rollers squeeze out much of the water. It then enters a dryer section, where the paper is dried by heated rollers and felts. At the “calendar section,” a continuous sheet of paper is smoothed under high pressure before being wound on large steel rolls. Samples are taken regularly, and the paper quality is carefully checked. Depending on its future use, the roll may then go through a sizing and coating process. Pepin explained that the Rumford mill manufactures paper for a wide variety of applications, including high-end magazines and catalogs, direct mail, grocery can labels, gift wraps, posters, book dust jackets, textbooks, and envelopes. [Editor’s Note: The paper in the magazine you’re holding comes from the Rumford, Maine, mill and a Verso mill in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin.] “Our uncoated product is used for newsletters and transactional documents,” she said.

During the tour, I saw signs in many of the buildings displaying the phrase “From Survive to Thrive.” I asked Janet Koski, the human resource manager, about this. She replied, “We’re not quite there yet, but we’re working toward it. Under new ownership, the outlook is long-term, and we are rebuilding the operation with that focus. We want to be around for 100 years.” Pinkham, who has worked for eight different paper companies, seemed to have a similar view. “Under Boise Cascade, I felt like I was on a winning team. After a long period of decline and bankruptcies, now I feel like I’m on a winning team again.”

A Local Legacy

Paper-making began in Rumford, Maine, in the early 1890s with the Rumford Falls Paper Company and the Rumford Falls Sulfite Company. Hugh Chisholm built the Oxford Paper Company facility on the current mill site in 1901. Chisholm got his start as a newspaper boy; he bought out his employer at the age of 16 and employed over 200 newsboys. He grew his newspaper and publishing business and became involved in the pulp-and-paper business. At the time Oxford Paper was established, Chisholm was the president of International Paper Company, then the largest paper company in the world. Oxford Paper began producing pulp in November 1901 and installed its first paper machine a month later. By 1902, the mill was producing 44 tons of paper per day using four machines. That year, the company secured a contract with the United States Postal Service to manufacture all of their postcards, and Oxford Paper was soon producing three million cards per day. Oxford Paper continued under Chisholm family ownership until 1967, when it was sold to Ethyl Corporation. It was then sold to Boise Cascade in 1976, and again to Mead in 1996. Mead merged with Westvaco in 2002 to become MeadWestvaco. It was sold to NewPage (owned by Cerberus Capital Management) in 2005 and then Canada-based Catalyst Paper in 2015. In 2018, it became the U.S.-based ND Paper LLC, a subsidiary of China-based Nine Dragons Paper Holdings.