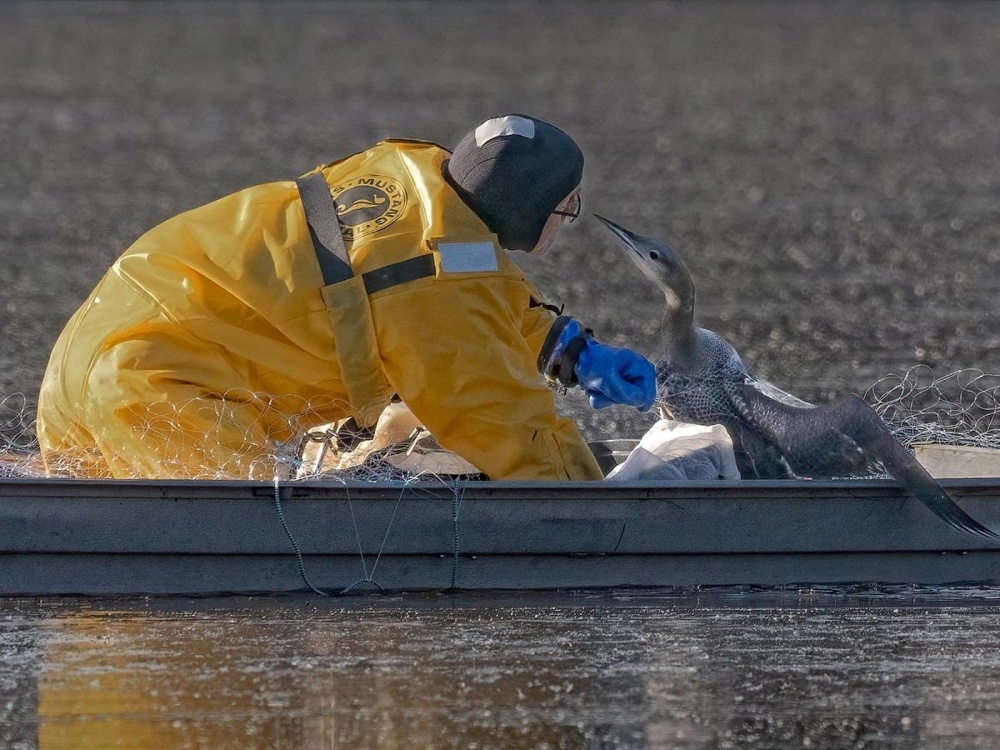

In the Winter 2024 issue of Northern Woodlands, writer Brett Amy Thelen describes heroic efforts to rescue stranded loons from iced-in lakes throughout the Northeast. With heavy bones built for swimming and diving, loons require a “runway” of approximately 100 yards to become airborne. Most migrate to the open ocean in late fall, but some linger on inland lakes due to inexperience, illness, lead poisoning, or “molt-migration mismatch” – a climate change–related phenomenon in which some of the cues that prompt loons to migrate (such as falling air and water temperatures) come too late in the year, when the birds are in the midst of molting their flight feathers and are therefore unable to fly. Whatever the reason, when loons fail to migrate in time, encroaching ice can trap and ultimately kill them.

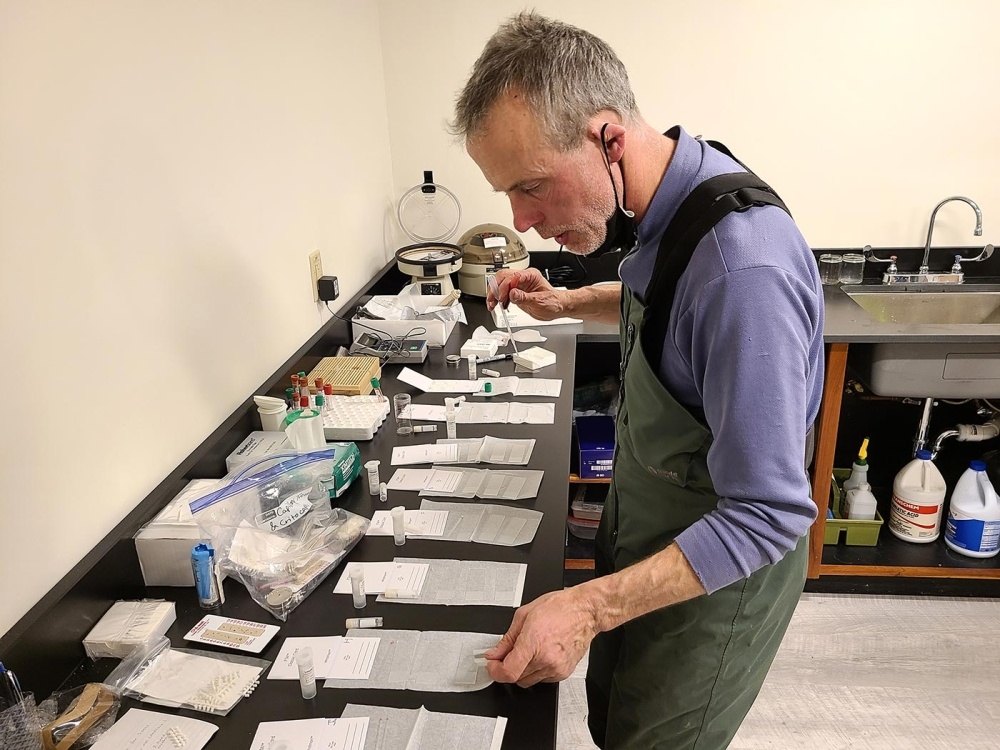

One of the challenges of preparing this article for print was choosing from among dozens of compelling photos and having to omit many for space constraints. Here’s a look at some of those photos – as well as a few that appeared in the print article – documenting rescue efforts on four different New England lakes.