Last October, in Weld, Maine, I hung from a rope in the canopy of a 41-year-old American chestnut tree on the property of author and naturalist Bernd Heinrich. The tree bore the scars of a honey mushroom infection from a few years back, but it otherwise appeared healthy, with a garland of pale green leaves at the end of every branch. It was a kind of living ghost, and I was climbing it to look for seeds.

For millennia, the American chestnut was one of the most common tree species of the Appalachian forest. Today, the tree is functionally extinct due to chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), a fungus introduced from Asia in the 1900s. Affected trees will sprout from their stump, grow to about 5 years old, then succumb to the blight again. These stump sprouts never live long enough to reproduce.

This made the tree I was climbing very special. Heinrich planted it in 1982, along with 14 other chestnut saplings, in the clearing beside his cabin. He had purchased the trees on a whim, after reading about them in a catalog for wild seeds collected by the Wexford County Soil Conservation District in Michigan. “I saw an ad for American chestnut trees,” he recalled. “So I said, ‘What the hell, I’ll order some.’ And I basically forgot about them.”

Over the years, most of these young trees succumbed to the normal trials of being a tree – including porcupine attacks and fungal infections – but none died of blight. Now only this chestnut and one other from the 1982 planting remain. Because they crosspollinate, chestnut trees require two trees to reproduce. And growing just a few yards from Heinrich’s off-the-grid cabin are two mature trees.

I shifted my weight to glance at the upper branches. The slanting afternoon light shimmered in the bright leaves as they jostled with my movement. The branches of these trees were laden with spiky burrs. Looking down into the forest that surrounded the cabin clearing, I could see bright green leaves of chestnut saplings in the understory.

I am a technical tree climber, a skill I learned at Hampshire College where I got my undergraduate degree in canopy ecology. At the time of my visit to Heinrich’s property, I was months away from finishing my master’s degree from the University of Vermont’s Field Naturalist Program. One of my professors in the program, ecologist Jason Mazurowski, had just published an article with Heinrich in the Northeastern Naturalist that described chestnut dispersal and regeneration at the Weld property. Their study of the site, which also included work by Lena Heinrich, Carolyn Loeb, and Robert Rives, represented a rare opportunity to track how American chestnuts spread across a forest outside the influence of the chestnut blight. Such basic information about the species is lacking, Mazurowski explained to me, because the blight arrived so early in the 20th century. “Chestnuts were gone before modern forestry,” he said.

The team’s observations arose from the growing seasons of 2019 and 2020 and built upon previous monitoring done by Heinrich. The Northeastern Naturalist article documented the effects of scatter hoarding, a process by which red squirrels and blue jays cache chestnut seeds underground throughout the forest to save food for the winter months. If the jays and squirrels don’t make it back to their caches, the seeds will germinate into saplings. With the assistance of these animals for transport, the chestnut saplings counted in the survey had an average dispersal distance of approximately 124 meters from the parent trees with a nearly 90 percent survival rate between the two growing seasons. In total, the scientists counted 1,348 trees, the second-largest known population of American chestnut trees in the country today.

Weld, Maine, is north of the historical range of the American chestnut, but climate change trends mean that chestnut trees can now grow where they couldn’t before. The findings in the Northeastern Naturalist paper may be especially helpful in the widespread effort by organizations such as The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) to repopulate northern New England forests with chestnuts, including areas outside of the tree’s historical range, where they could potentially avoid the influence of the blight.

Mazurowski wants to be a part of that effort, too. He explained that he wanted to bring seeds back to Vermont and raise seedlings in his native plant nursery. Propagating chestnuts on the landscape can help preserve whatever genetic diversity is left of the species. Meanwhile, TACF and other organizations are working on crossbreeding the American chestnut with the Chinese chestnut, which is naturally resistant to the blight, to produce hybridized trees that could survive in a blight-infected forest. There is also an effort in progress, initiated by TACF’s New York chapter and the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) to use biotechnology methods to add blight resistant genes to the American chestnut genome. If such efforts succeed in producing blight-resistant trees, the American chestnuts from Weld could cross-pollinate with these trees and reincorporate a small fraction of the original genes into the new population. But first, Mazurowski needed to collect the seeds before the blue jays and squirrels took them.

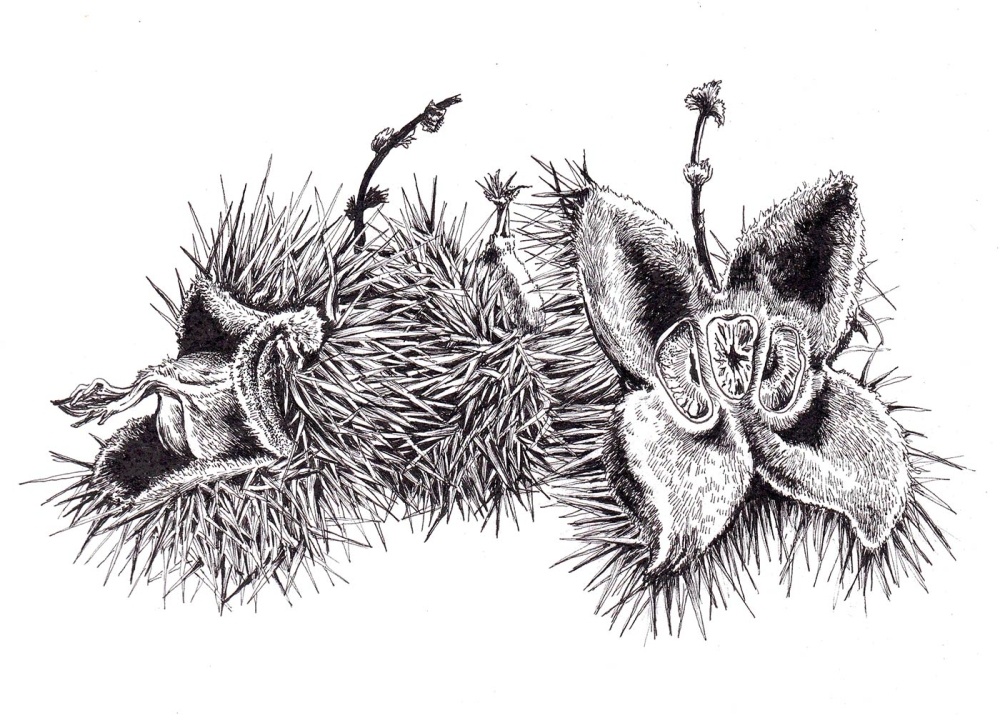

Usually, Heinrich patiently watches the clearing outside his cabin throughout October for the day that the chestnut seeds are mature and ready to drop. He is part of a three-way competition. Blue jays pry open the ripening burrs and stow up to three seeds at a time in their bills before flying away to cache them somewhere in the forest floor. Squirrels snip off the burrs from the trees and drop them to the ground, where they complete the work of extracting the seeds before running off to fill their own caches. As for Heinrich, he lays a tarp at the base of the trees and waits for the squirrels to drop the burrs.

“And then he goes and scares the squirrels away and scoops the seeds into a bucket,” Mazurowski said. In 2018, Heinrich collected thousands of seeds this way. “We came up and he had a party, with a bunch of people up at the cabin, and we were just roasting the seeds, eating them,” Mazurowski recalled. There were “buckets and buckets of them...he was giving buckets [of seeds] away to people.”

In 2022, Mazurowski also hoped to get buckets and buckets for his nursery. Heinrich had reported a good flowering year but explained that he wouldn’t be able to help collect seeds, as he would be away from the cabin at harvest time. Because Mazurowski could only spare a day from his schedule to collect seeds, he decided to take the blue jay approach and collect burrs directly from the tree. Which is why he invited me to Maine.

So, I wrote an out-of-office email, skipped class, and packed my car with my climbing saddle, rope, and helmet. I met Mazurowski at his house in central Vermont, before the autumn sun had burned off the morning fog. Despite the early start, the energy in the car was palpable, an excited and nervous buzz. It had only been three days since Heinrich contacted Mazurowski to warn him that the seeds were opening, but we were worried that we were still too late.

Four hours later, we arrived at the steep, washed-out road to the cabin. We parked at the bottom and arranged our gear to carry it up. We decided to bring three buckets. There were two more in the back of Mazurowski’s car, just in case.

From 30 feet up from the ground, I took stock of the thickness of the branches overhead and threw my rope into the crown of the tree. I transferred my weight onto the new branch and climbed higher. From the next branch up, squinting into the sunlight, I saw that what we feared from the ground was true: every single seed casing was either empty or had already been snipped off the tree. The blue jays and squirrels had gotten there first.

Mazurowski, a tall, wiry, ultra-runner with contagious energy, was unusually quiet as he stooped below the tree to dig through the duff. I traversed across the branches to shake some of the husks to the ground to him. “Anything?” I asked from the canopy. “Nope,” said Mazurowski, dropping a peeled-open husk back to the ground. I pulled out my binoculars to take a closer look at the other tree from my heightened vantage point. No seeds.

Mazurowski dropped to the forest floor on his hands and knees. He was desperately pulling apart husks with his bare hands and searching for single seeds that a squirrel might have extracted but forgotten. The wind picked up, stirring up the smell of earthen decay on the brisk fall breeze. Dappled sunlight danced across the ground. As I rocked gently back and forth in the swaying branches, I took a moment to appreciate the beauty of the canopy of long-toothed leaves that I had only ever seen previously on stunted, blight-infected stumps.

“I found one!” Mazurowski exclaimed, sitting up in a triumphant pose on his knees in the duff, hands covered in mud, chestnut husk spikes embedded in his fingers. He held up a quarter-size, plump, brown seed. As I continued to explore the branches of the tree, Mazurowski located nine more seeds in the duff. When I descended my rope, he was holding all the seeds – our entire harvest – in the cup of his hands.

We packed our things and headed up the path toward the cabin. When we passed by one of the offspring of Heinrich’s original chestnuts, Mazurowski stopped to inspect its branches. The 20-year-old tree had flowered for the first time that year. There, on one branch, was a single enclosed green bur. Mazurowski smiled as he pulled out his pocketknife and extracted two seeds from the husk. Two generations of seeds, he explained, means much more genetic diversity.

When we entered Heinrich’s cabin, Mazurowski found a Ball jar to put the seeds in, but he kept the two grandchildren seeds separate. He sighed as he screwed the lid shut and placed the jar on a table. The sun dipped behind the ridge, casting the cabin in darkness as he turned to stoke the wood stove. We covered our disappointment with the methodical acts of making food and conversation, swapping stories across a table etched with the names of the many ecologists, writers, and others who had visited the cabin before us.

By the next morning, Mazurowski had worked through his disappointment. “We didn’t collect many seeds. That only means there were that many more planted in the forest, right?” he said. A single blue jay, he noted, could cache 4,000 seeds in a single season. So, if that jay gets eaten by a hawk, that’s 4,000 trees that were planted, some of them miles from the parent tree.

Bernd Heinrich started with 15 chestnuts, and 2 survived to reproduce. “And now there’s nearly 1,500 young trees,” Mazurowski said. “So, yeah, I might only have a dozen or so seeds, but who knows?” Packing the seeds carefully into his bag, he added, “I don’t know if any of these will make it to reproductive age, but if I end up with two reproductive trees, I could end up with a forest, too.”